Point: You should vote

You should vote.

Often when people tell you that, they argue it’s a sacred responsibility and the best way for you to effect change. Voting advocates tend to get a little hyperbolic.

I won’t attempt to list activities from most to least impactful in terms of bringing about change, but I will readily acknowledge that voting isn’t the only way to do it.

There are other things you can do, other tools in your social change toolbox. Any good organizer knows you need diverse strategies and tactics at the ready if you’re hoping to bring about any type of societal improvements, but voting doesn’t hinder those other efforts in any meaningful way. You can do both.

For the conscientious non-voters

Many of smartest and most well read people I know practice radical politics, identifying as socialist, anarchist, or communist. They do so because they recognize the structural inequalities that exist in society and want to address them.

They further recognize that voting isn’t a panacea for all of a country’s problems and inequalities – a new democratically elected government won’t change the nature of our capitalist world-economy and it won’t end the burning of fossil fuels. Where many of them err is rejecting voting or otherwise participating in the electoral system as naive, inconsequential, or a waste of time.

Many of those radicals view our elections as something akin to electing a new captain to steer the Titanic after its collision with an iceberg. They see us headed in a terrible direction and the matter of who leads us as an entirely superficial or cosmetic decision at best, or a distraction from the real issue at worst.

I encourage you to remember that even small changes can have a big effect – particularly when stacked one on top of the other. When their effect is to stigmatize groups, decrease accessibility of essential services, or ravage the environment, they can worsen the lives of many people. When they’re targeted at alleviating poverty, making services more accessible, or reducing harm to the environment, these gradual changes can have the opposite effect. Passing on electoral politics is effectively giving in to the former as an inevitability.

Government has had a major impact in alleviating inequality in other countries. Scandinavia, where a social democratic agenda has prevailed through much of the late 20th century, is full of examples. In Finland, a government-run “housing first” initiative helped to reduce the number of homeless people in the country from over 18,000 in 1987 to 9000 people in 2003 – effectively dropping the country’s homeless rate by over 50 per cent in the span of 15 years. The housing policy didn’t end homelessness altogether, and Finland, like every country, still suffers from economic inequality, but for those lives that were improved by government intervention, it wasn’t an inconsequential difference.

We don’t have to go far to see the impact of government policy. Canada’s history is full of policy changes and political decisions that have had both great and terrible effects for its citizens. We’ve established a national healthcare system, created the CBC, and passed a law allowing same-sex marriage.

We’ve also had a long history of colonization, sent young people to die in wars, plundered our natural resources, and infringed on people’s rights – putting Japanese Canadians in internment camps throughout the 1940s, for example. National childcare, legalization of marijuana, housing initiatives, and a variety of other policies are currently on the table. Which of these things we do and who is elected to implement other legislation moving forward does matter.

You may not like the fact that someone else is producing legislation that will impact you, but this will happen whether you vote or not. And if you don’t vote, then it’s that much more likely to be someone you find unpalatable and who has a drastically different view of the world.

The perfect as enemy of the good

Conscientious non-voters often point to the fact that no party perfectly represents their ideal government (or even form of governance) as a reason to reject the system altogether. The perfect is the enemy of the good, as the saying goes.

Many people prefer being involved in social movements – such as the Occupy movement, Idle No More, or the student movement – where rhetoric is often high and there are greater opportunities to feel active and involved to electoral politics, which can be boring, unimaginative, and unpleasant on the whole.

Social movements give an opportunity for people to gather, discuss their problems, imagine an improved and often ideal world, and present that to the broader society, usually by taking steps to live their ideals in the public spotlight. It’s a beautiful thing to see.

Radicals are right in that social movements play a major role in bringing about social change. In fact they’re generally the prime incubators of social change. But it’s through government action that these changes are often institutionalized, ensuring that the new ideas that have been concocted and any benefits that have been won remain available well into the future, after the movement has fizzled.

So organize a sit-in or boycott, write slam poetry, support alternative media, and found a workers’ co-op. Live the way you want to live. And when all that is done, pop in to a local voting station and mark an X beside the candidate you think is best suited to make a difference.

Voting won’t change everything, but it will change some things – don’t throw anything out of your toolbox just yet.

Craig Adolphe is the editor-in-chief at the Manitoban

Counterpoint: Don’t vote

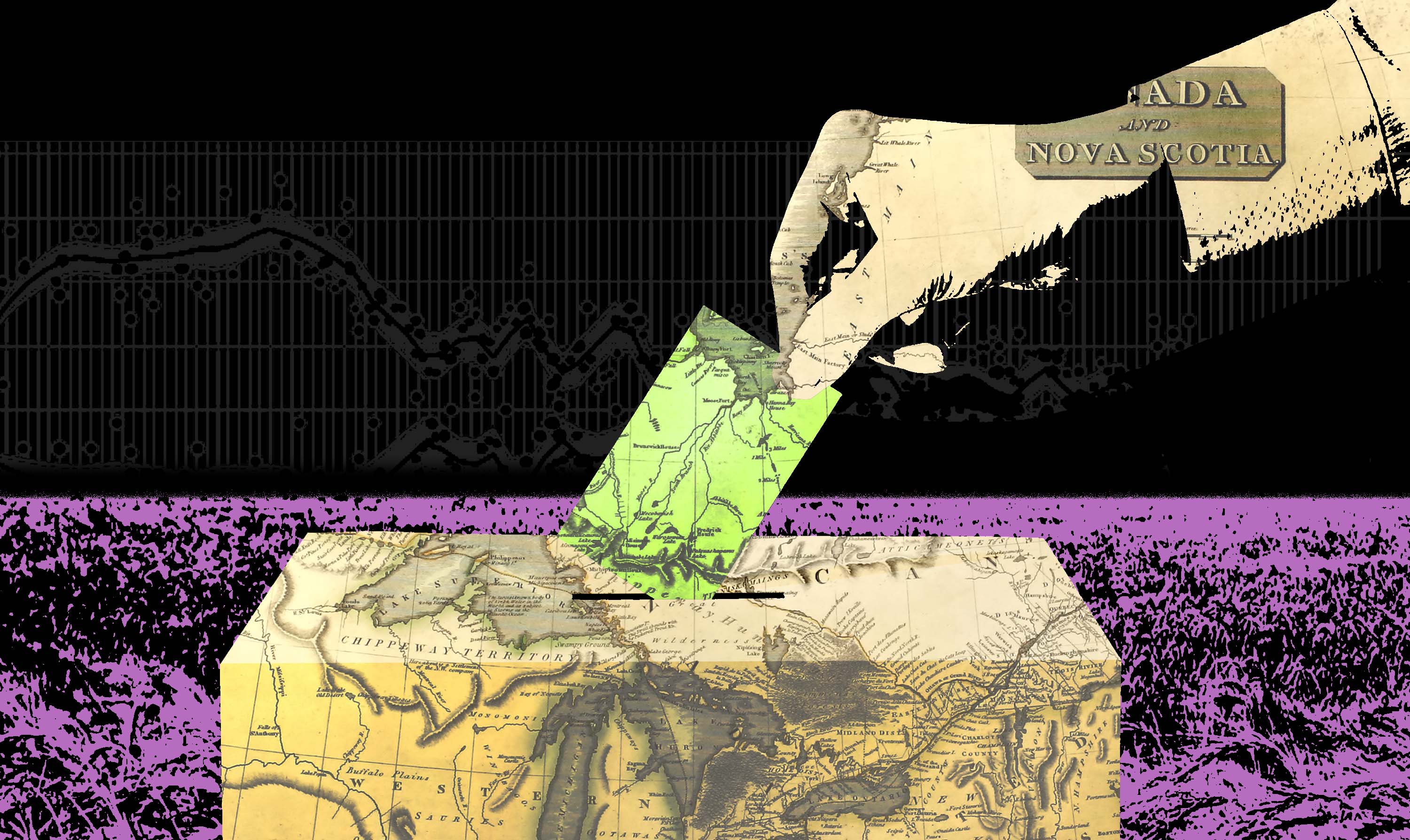

Voting is nothing. Voting is checking a box on a piece of paper.

Not many people bother to check that box anymore. We are told that this is a bad thing. We are failing the system, our country, our society. Somehow, if more people checked that box, things would be better.

Not voting does not mean that you are apathetic, though certainly many people who do not vote are. But this is also true of many people who do vote – whose sole act of civic engagement is checking a box every few years.

Many people vote for the same political party their entire lives without knowing the candidates, the issues, or even the history of the party they are voting for. Is their uninformed participation in the system, which is easily manipulated, better than my informed lack of participation?

To hear voters wax poetic in their defence of voting, you would think it was an informed debate among equally reasonable and knowledgeable peers. Images of white-robed Greeks, sage and bearded, are forced upon the imagination of the unfortunate listener.

Be the most well-informed, reasonable person you can be. But remember, when you check that box, your vote counts no more than the most gullible, hateful, criminal, stupid, and bigoted members of our society. Or, if you prefer, their worldview is just as valid as yours.

Not voting does not mean that you are happy with the way things are. Neither does voting, for that matter. “Change,” “hope,” and “better” are familiar clarion calls which tend to make people flock to a certain political banner. But not voting can stem from an understanding that the real issue is not the party in power – it is the system through which that party holds power.

If you think that the system itself is deeply flawed and must be replaced by a better one, then why would you debase your ideals by participating in that flawed system?

In particular, why would you give up your sovereignty by voting? That’s what voting is – the acquiescence to be ruled. If you vote in good faith, that democratic act is a two-way street. If your candidate doesn’t win, you must submit to the authority of whoever did win. A vote for any candidate is a vote for the system. A vote for any set of ideals is a vote for our current system of government, be it a shade more blue, red, or orange.

The ideals may be different, but the system claims the authority (though it may not always exercise it) to tell you what substances you can put into your body, what are the permissible forms of worship, and what forms of expression are permissible. It will always claim the authority to practise violence on your behalf, punish on your behalf, steal on your behalf, and oppress on your behalf. A vote is merely an expressed opinion on how crudely enforced that authority will be, and in what walks of life.

That’s giving a lot away by checking a box.

Futility

Incremental change is often held up as a reason to vote: if the system itself is bad, the line goes, than at least we can slowly make it better, because incremental improvement is better than nothing. This would be an attractive argument, if incremental changes were always improvements. But a system that can be made incrementally better through voting can be made incrementally worse in the same way. Incremental change is nothing other than the lack of ability on the part of the system to resist capricious change by the government of the day.

In Canada, we’ve seen incremental improvements in environmental regulations over decades, which have been, inarguably, a good thing. But by the very mechanisms these improvements were accomplished, they were swept away. The system allows for tinkering, but there are no methods to guarantee this tinkering will be for the greater good. Rather, the tinkering is most likely to be done by the kind of unscrupulous people who are best at manipulating others to vote for them. These changes are most likely to be done so that these unscrupulous people can cement their hold on the system.

Not voting does not mean you are not involved. If you do not vote on principle, then you have a moral responsibility to be involved, at least to the degree that you must live your life in accordance to your own ideals. There is greater involvement, and probably greater effect, in a person trying every day to be kind, charitable, environmentally conscious, and socially responsible, than voting can ever bring.

Not voting means living your life well without needing to elect someone to tell you – legally compel you, more likely – to live your life well. It means opening yourself to your own personal shortcomings without having the government as a whipping boy to shift blame to when you fall short.

On a practical note

The system is broken. It will, for many years, prop itself up, whether you vote or not. In nothing is this seen more clearly than in its response to climate change.

Climate change is a threat to every human on the planet, one that cannot be ignored or stopped. To avoid the worst of its effects – and the worst of its effects may be the collapse of the biosphere and the end of human life – will require massive cultural, economic, industrial, and social re-organization on a global scale. However, the people you could vote for refuse even to speak in the language of radical need – they lack the will and ability to begin the necessary adaptations. The system cannot even address the impending collapse of the life-systems which support its constituent parts – which it glibly calls “voters.”

Not voting is recognizing the huge disconnect between our government and our lives, between reality and pleasant fiction, between the lies of politicians and the truth of your conscience.

Don’t vote – don’t waste your time. Live your life in such a way that if everyone lived their life like you, we wouldn’t need to cast a vote deciding which of your brothers was least unfit to be your keeper.

Evan Tremblay is the comment editor at the Manitoban