The smell of rain is earthy and distinct. Raindrops splatter against the ground and release earthy odourant molecules into the air, but the exact mechanism of this event hasn’t been elucidated until now.

Recent research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology sheds light on exactly how rain spurs these hidden Earth smells.

In their study published in Nature Communications, mechanical engineers Young Soo Joung and Cullen Buie took to observing drops of water as they hit porous materials using powerful high-speed cameras.

As the simulated raindrops hit the materials, small bubbles of air formed at the contact point, rose through the body of the drop, and fizzled out of the top, forming aerosols. This phenomenon was observed upon synthetic materials, as well as soil samples.

As the bubbles fizzled away, they released bits and pieces that it picked up from the soil. Not only could odourant molecules that we associate with the smell of rain be aerosolized, but so could soil-dwelling bacteria and viruses.

This process is very quick, occurring on the magnitude of one-millionth of a second. The formation of bubbles only occurs during light to moderate rain. Raindrops during heavy rainfall move too fast for this process to occur.

Petrichor is a term coined by Australian mineralogists in the 1960s describing the earthy smell that is liberated from the ground during rainfall.

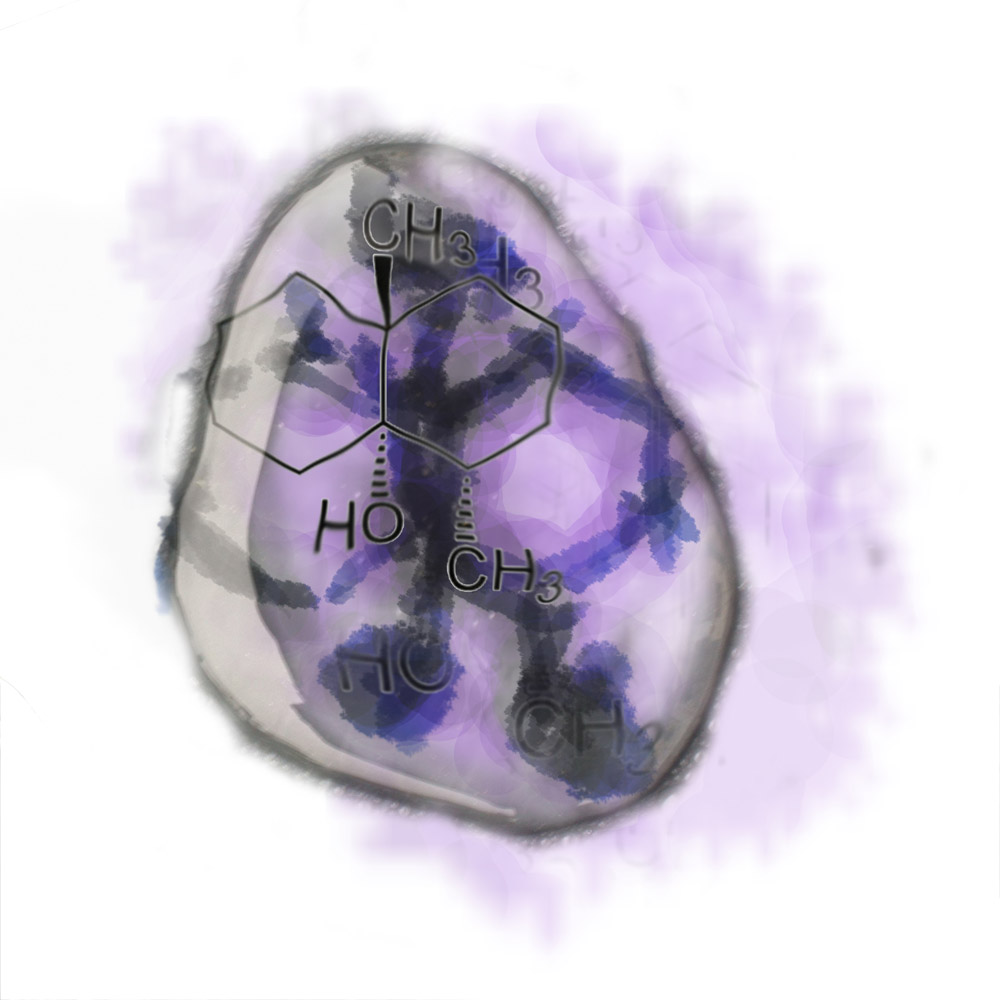

One of the molecules responsible for rain’s earthy aroma is the organic molecule geosmin. The molecule tends to stay suspended in the air after a storm passes, and is responsible for the earthy post-rain smell.

Geosmin is synthesized by Streptomyces bacteria, which also produce the majority of naturally sourced antibiotics that we use. Besides the earthy smell of a storm, geosmin also contributes to the flavour of beets.

Humans are able to detect geosmin in the air as diluted as five parts per trillion. That’s the equivalent of three seconds per 100,000 years. This sensitivity may be due to the fact that our ancestors relied on rain for its life-bringing properties.

Before a storm, a different scent fills the air. Ozone is formed in a series of chemical reactions trigged by lightning in the sky. Atmospheric nitrogen and oxygen are split apart and react to form the ozone molecule, which is made up of three oxygen atoms. Ozone’s name is derived from the Greek word ozein, which means “to smell.”

Unfortunately there is no hope of scenting summer storms in the midst of a Winnipeg winter. We can only long for petrichor.