As we begin to set up our non-denominational holiday trees and paint the words “season’s greetings” in our windows, we are about to be inundated with tiresome arguments about the secularization of the holiday season – why it’s a terrible thing that must be stopped, and why it’s a great example of the progress made by Western culture.

These articles write themselves, so there is not much point in reading them. They are two complementary examples of meaningless noise due to obsessive thought patterns in our public discourse. Whenever you see one of these incessant, insoluble debates in the media, there’s probably some underlying confusion or manipulation going on.

First of all, let’s get a few things straight: whatever one thinks of a pluralistic society, as a matter of pragmatism in a place where you can’t make any assumptions about the religious adherence of a stranger, it is useful to be able to say some insipidly pleasant phrase such as “happy holidays.”

And, conversely, the verbal acrobatics that must be performed to avoid mentioning Christmas even when it is clearly being talked about are a little absurd, rather like characters in a 1950s sitcom using elaborate euphemisms to avoid saying the word “pregnant.”

So saying “happy holidays” is dumb, but polite and harmless. There is no reason to get mad at your Walmart greeter. The phrase is nothing to be alarmed by; it’s just a way for people from many different backgrounds to get along during the holiday season.

What I am alarmed by instead is this artificial notion of a holiday season. When I was about seven, I recall my school putting up posters with the names of various holidays along with drawings of stereotyped children celebrating these holidays. There was one for Christmas, Hanukkah, Kwanzaa, Ramadan, and Diwali, and possibly others I’ve forgotten.

The point of these posters was obvious: they were designed to instruct us in the ways of pluralistic society, portraying our own (mostly Christian or pseudo-Christian) observances as only one possibility among many.

They did a good job of teaching us that others could be very much like ourselves. But I think it was perhaps too good a job, which left us unable to conceive of people who think much differently from ourselves. And we were well-fed, clothed, predominantly white kids living in a very safe part of the world and reasonably assured of a prosperous future.

These holidays are all very different. They occur in all parts of the year and are of widely varying length. Some of them are inextricably attached to a religion, some are rooted in old traditions but not necessarily religious, and some have gone over almost entirely to the commercial machine.

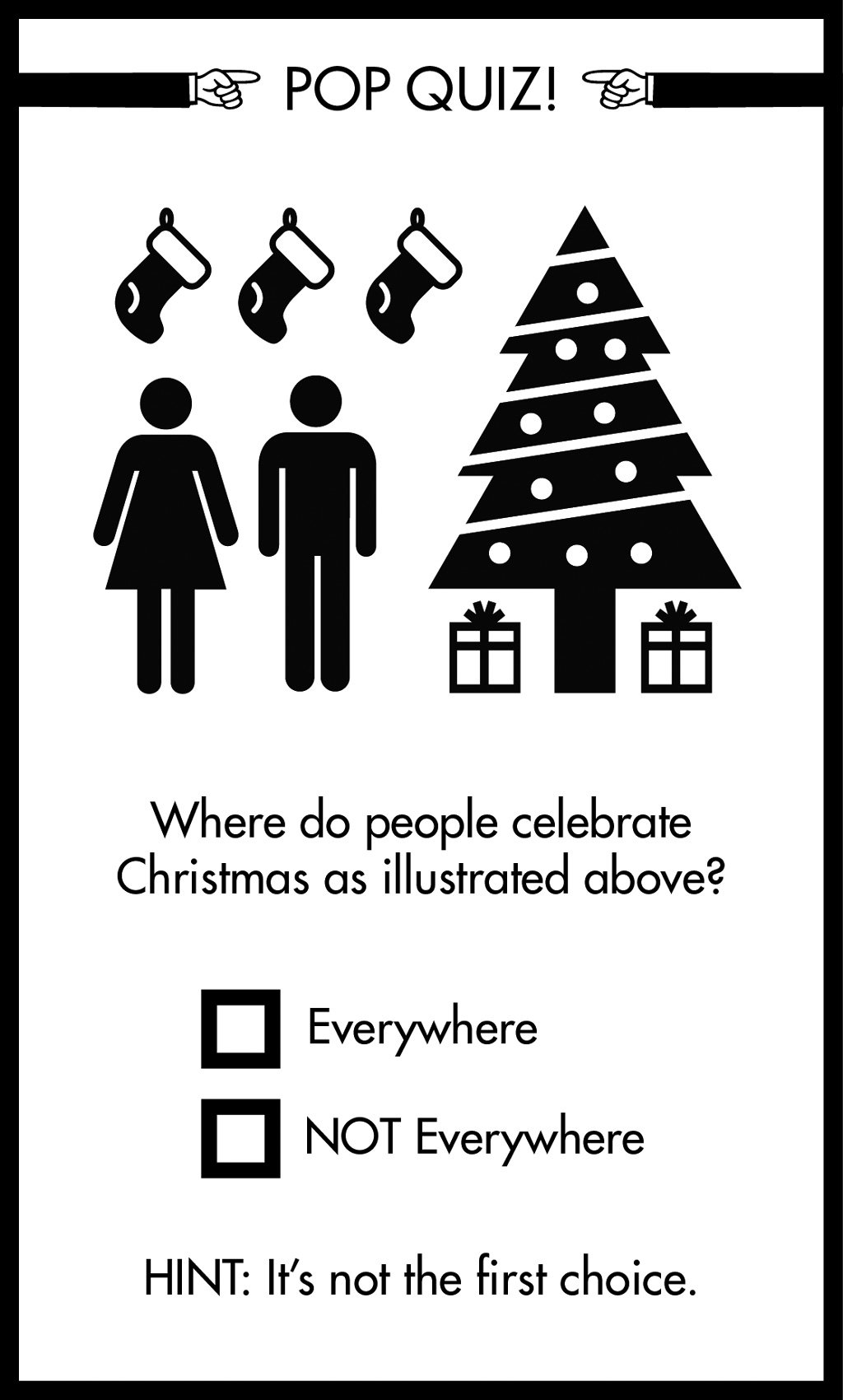

But to hear all the talk of a “holiday season,” or to see the posters hung in elementary schools, you would think that these very different observances were all merry late-December feast and gift-giving days differing from Christmas only in the date and some of the decor.

This has the effect of collapsing all cultures down to one in our minds. We are taught to think of people from other cultures like the aliens in Star Trek who are exactly like the Earthlings in all respects except for wearing an unusual hat. Most of us have given up xenophobia, but we have replaced it with xenoscepticism, which is scarcely an improvement.

The idea that a religion embodies the fundamental principles of a way of life is alien to many North Americans. The idea that these principles might differ from what we are used to in important and complicated ways is even more so.

But assuming that all cultures are minor variations on our own makes a lot of world events unintelligible. And, paradoxically, it weakens our sympathy for the rest of humanity who cannot get over such petty differences as what date to hold the December feast and buy each other televisions and microwaves.