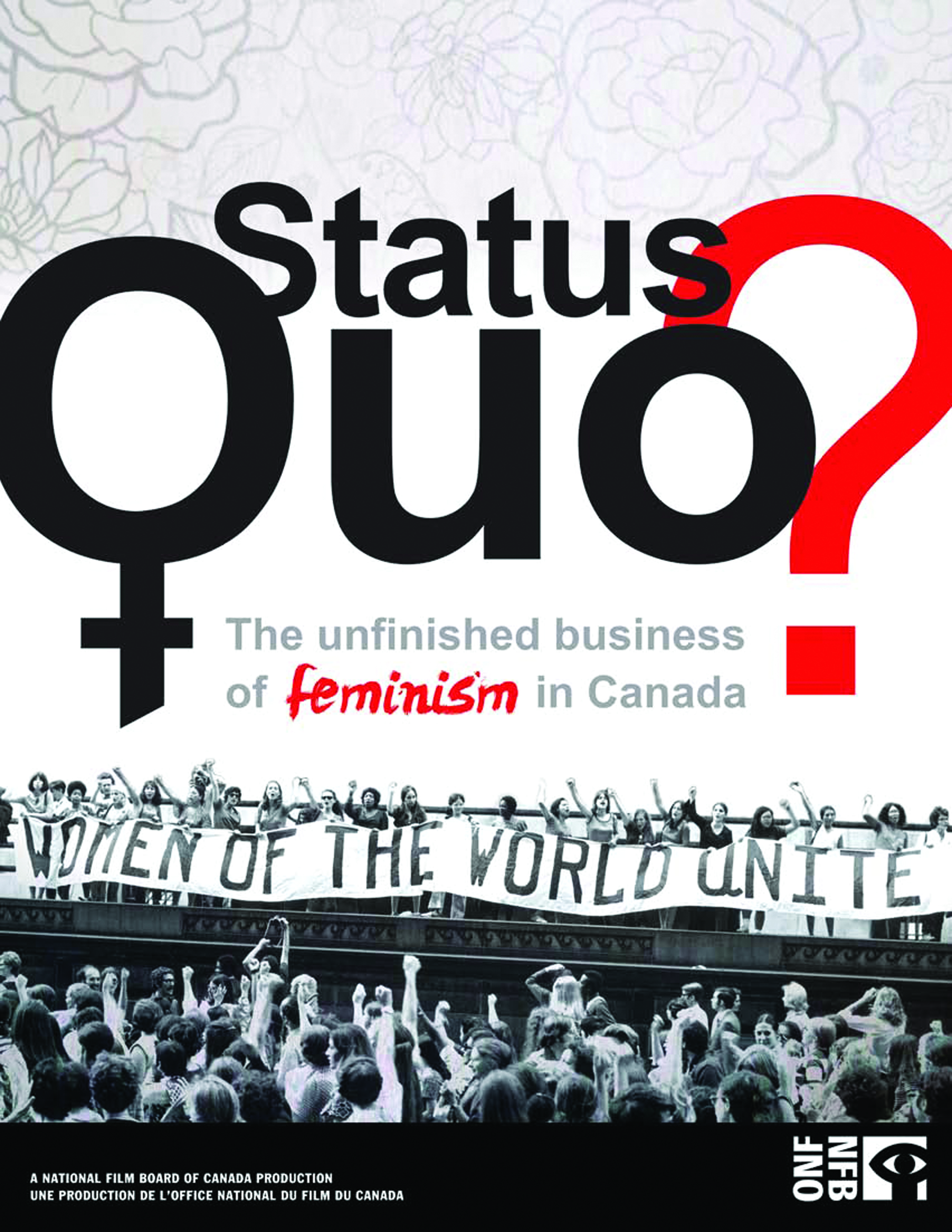

The opening scene of Status Quo? The Unfinished Business of Feminism in Canada interchanges and overlaps footage from the first Royal Commission on the Status of Women hearings in 1967 and the 2nd Pan-Canadian Young Feminist Gathering in 2011 in Winnipeg. While it’s striking how deftly director Karen Cho weaves together the similar images of what women gathering looks like, she’s able to even more shockingly show us how similar the attitudes of society and the struggles are many years later.

How have things changed for women in Canada? Have they changed at all? This film explores those questions.

Status Quo? examines some of the most pressing issues of modern feminism: domestic violence, missing and murdered Aboriginal women, abortion access, domestic international worker struggles, and reproductive justice (including mothering resources and daycare). The film not only covers decades of the struggles of women, but puts individual human beings on screen instead of just speaking about them broadly.

Putting faces to the issues at hand makes the struggles of women irrefutable. Cho shows women who are personally affected by laws and policies put in place by the government as well as the attitudes of society, a brilliant directorial choice.

The ideas and struggles documented are apt and relevant for our political climate. Under the Harper Government, women’s initiatives have suffered a huge blow; “equality” was removed as an objective in the Status of Women Canada’s mission statement, funding for independent research projects as well as advocacy and lobbying (all funded by Status of Women Canada) experienced a 100 per cent research cut, the Aboriginal Healing Foundation and the Sisters in Spirit Initiative were defunded, the pan-Canadian childcare funding ($1.2 billion) was revoked, and 12 out of 16 regional Status of Women Offices were closed.

These points are noted in the film and some are illustrated through the personal experiences of women and those who do the work affected by these cutbacks. However, I feel that Cho really misses the mark when it comes to linking the issues and demonstrating the intersectionality that modern feminism acknowledges and thrives on – at least, concretely.

While it’s suggested and hinted at abstractly, Cho never really spells it out for the viewer. While some may like the ability to connect the dots, I worry that those new to feminism or non-feminist viewers might miss the importance. In an age where Sady Doyle’s decree that, “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit,” has rung out loud and clear as the mandate for this wave of feminism, I do think that making this connection for the viewer falls short.

The film features many scenes from the RebELLEs gathering in 2011, which serve as optimistic and inspirational aside from the harrowing discussions and facts that show the real current status of women. They also serve as bookends and dividers between the segments, so their utility is understandable. However inspiring and hopeful, these scenes do feel a bit disjointed with the rest of the film and their subject matter doesn’t necessarily correspond with the issue being discussed prior to their inclusion. I understand the importance of including this material and the role that it plays in the film, I’m just uncertain about where it’s placed.

Regardless of my critiques, this film is an absolute must-see and eye-opener. Even for those who consider themselves well-informed, you can’t really grasp many of the realities behind that information until you hear it from the mouths of the women affected. It’s one thing to know how difficult it is to attain an abortion under the stringent laws of New Brunswick, but it’s another to hear women who have tried talk about how difficult it was.

My hope is that this film will leave skeptics and seasoned feminists alike realizing how relevant feminism still is in today’s society.

You can watch Status Quo? The Unfinished Business of Feminism in Canada at nfb.ca/international-womens-day.