My ‘birder’ origin story

My name is Bryce Hoye, and I am a “birder.” We come in a variety of morphs, us birders: some are cut from the backyard bird-watching cloth; other, more ambitious and serious lifelong birders — adorned in the Tilley hats, Birkenstocks, binoculars, and bird books characteristic of the birding community — plan entire vacations in accordance with, say, the prospect of catching a significant migration event, perhaps venturing to areas known to present rare and fleeting glances at endangered species.

I classify myself somewhere along the lines of a “wandering bird biologist” on this spectrum, as a great deal of time over the past six years of my life has been consumed by ornithological field work across Canada.

I wasn’t always bird-brained. Birds were once just the pleasant and non-intrusive background noise of my adolescent years. Summers were spent at the cabin in northwestern Ontario, being capriciously led about the surrounding woods by a budding, though unfocused, spirit of natural inquiry.

The creatures of the boreal forest beguiled me in those frenetic, formative years, and continue to do so. A series of contract positions to follow working with the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), as well as other agencies, wrought an interest in the avian component of wildlife and conservation biology, specifically.

The summer between my first and second year of university, I managed to land a seasonal position with the local Winnipeg branch of the CWS conducting surveys for the elusive marsh-bird species, the Least Bittern. As well as banding, trapping, and swabbing the cloacae (or hind quarters) of hundreds of waterfowl for avian influenza in the month of August, most of that summer consisted of me and a species–at-risk wildlife biologist (def: a biologist focused on studying wildlife species threatened or otherwise “at-risk” of becoming endangered) living out of the back of a truck, scything across Manitoba’s prairies and wetlands in search of Least Bittern populations.

Six years hence and all but one of my past six summers have been devoted to chasing after eccentric biological field research positions studying birds across Canada. And that chase sustains me as much as any interest in the birds themselves.

I’ve had the privilege to spend a summer on a crew monitoring how the Ovenbird, a ubiquitous species of wood warbler, is responding to the seismic and pipeline development going on in the southwestern-most reaches of the Northwest Territories. Another field technician position transplanted me to an island off the coast of Nova Scotia, living amidst the ceaseless raucous of over 1,200 colonial nesting Arctic, Common, and Roseate terns. This position entailed performing predator deterrence (i.e. scaring away crows, gulls and birds of prey with pyrotechnics) and monitoring the tern chicks’ feeding and mortality rates. And yet another summer occupied by breeding bird surveys and ecological vegetation sampling in northeastern Alberta, employed by the Alberta Biodiversity Monitoring Institute.

Perks of bird-work

Time and again this unorthodox career path has come with a suite of fringe benefits: for instance, facilitating the wanderlust of my early 20s. They’ve provided me with a license to explore and immerse myself within the beautiful remote boreal forests and bogs, cat-tail ridden wetlands, and salty Atlantic coastal areas that comprise but a part of Canada’s excessively rich natural landscapes.

The adventure has given me a way to build on and file impressions of nature in the style of some of my naturalist heroes — like the gaunt wanderer, nature-activist and creator of the Sierra Club, John Muir.

According to the Sierra Club, he once described himself as a “poetico-trampo-geologist-botanist and ornithologist-naturalist etc. etc. !!!!” This is really just to say he was a glamorizer of nature, and kept some of the most brilliant anecdotal descriptions of nature in his field diaries. Of course, it is self-flattery of a heinous degree to make even an oblique comparison between myself and a man who pioneered wildlife preservation and natural heritage appreciation in the U.S.A. “His writings contributed greatly to the creation of Yosemite, Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest, and Grand Canyon National Park,” states the Sierra Club’s webpage.

Privileged as I’ve been to be where I’ve been, these birdie-experiences have simultaneously conferred unto me a deep consternation at what Richard Louv refers to as “nature deficit disorder” in the general public. And, oh, how epidemic the scale! But that is a lamentation for another time.

Notes from the western boreal

It has been a dream of mine, mounting for some time now, to record and share some of my own field journals. For now, I will leave you with the first of several entries from my field journals this summer, logged on May 29 from Lakeland Provincial Park, Alberta.

May 29, 2012:

The glassy, ascending spiral song of a Swainson’s thrush; the quarrelling, buzzing trills of two chipping sparrows; and the abrasive honk of a redneck grebe carry across the gentle surface of Touchwood lake. Those tentative first revs of the dawn chorus spilled in through the vestibule of my tent without invitation at 3 a.m. this morning, and to my delight, I knew immediately who they were coming from.

Eight others and myself have been preparing for this day for over a month now, listening to hour after hour of recorded birdsong from Jim and Barb Beck, Jim Butler, John Neville, and Monty Bringham. Today marks the end of our official training period, and we are now setting off to our respective corners of northern Alberta for the next two months of boreal breeding bird surveys, also known as “point-counts.”

Point-counting consists of going to various predetermined habitats (usually by some principal investigator of a stud), at the crack of dawn (sometime between 4 and 5 a.m.), and identifying what species of birds are present through their signature songs. A good analogy is to think of birds’ songs as their fingerprint; each song unique to a species; each species’ song with it’s own dialects variable dependent on geographical locations.

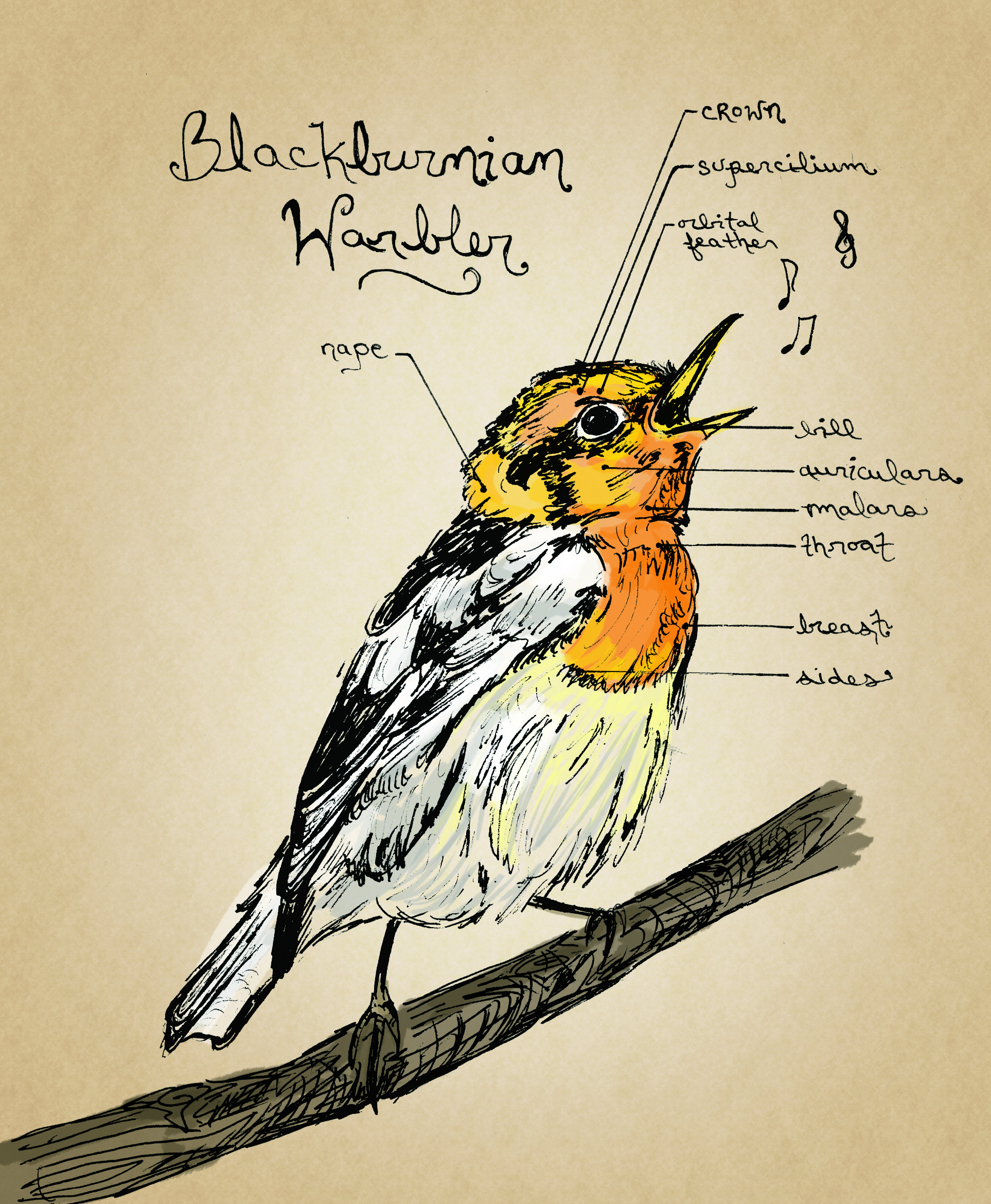

We arrived to Touchwood Lake with promises from our principle investigator of seeing some of the rarest, most vibrantly coloured species of warblers of Alberta during our training period. True to her word, splotches and streaks of brilliant yellows, oranges and greens flitting around, projecting songs from atop the conifers of our campsite. The Cape May and Bay-breasted warblers sang the thin, high-pitched “seet seet seet” and “se-seew, se-seew, se-seew” phrases that make them next-to indistinguishable from each other by song alone.

The highlight by far was hearing the distinctive “tseekut tseekut tseekut tseee” song and seeing the flamethrower-orange breast, throat, nape, lores, and supralorals of the Blackburnian Warblers. It took six, exhausting days of literally living beneath a breeding pair to finally catch a glimpse.

Wow. I am such a bird nerd.

ILLUSTRATION: LAURA BOULET