Since the advent of space exploration, cosmic images have been a vital source of information for us. Jayanne English, an associate professor in the department of physics and astronomy at the U of M, recently took second place in an international contest with her own depiction of a far-off galaxy.

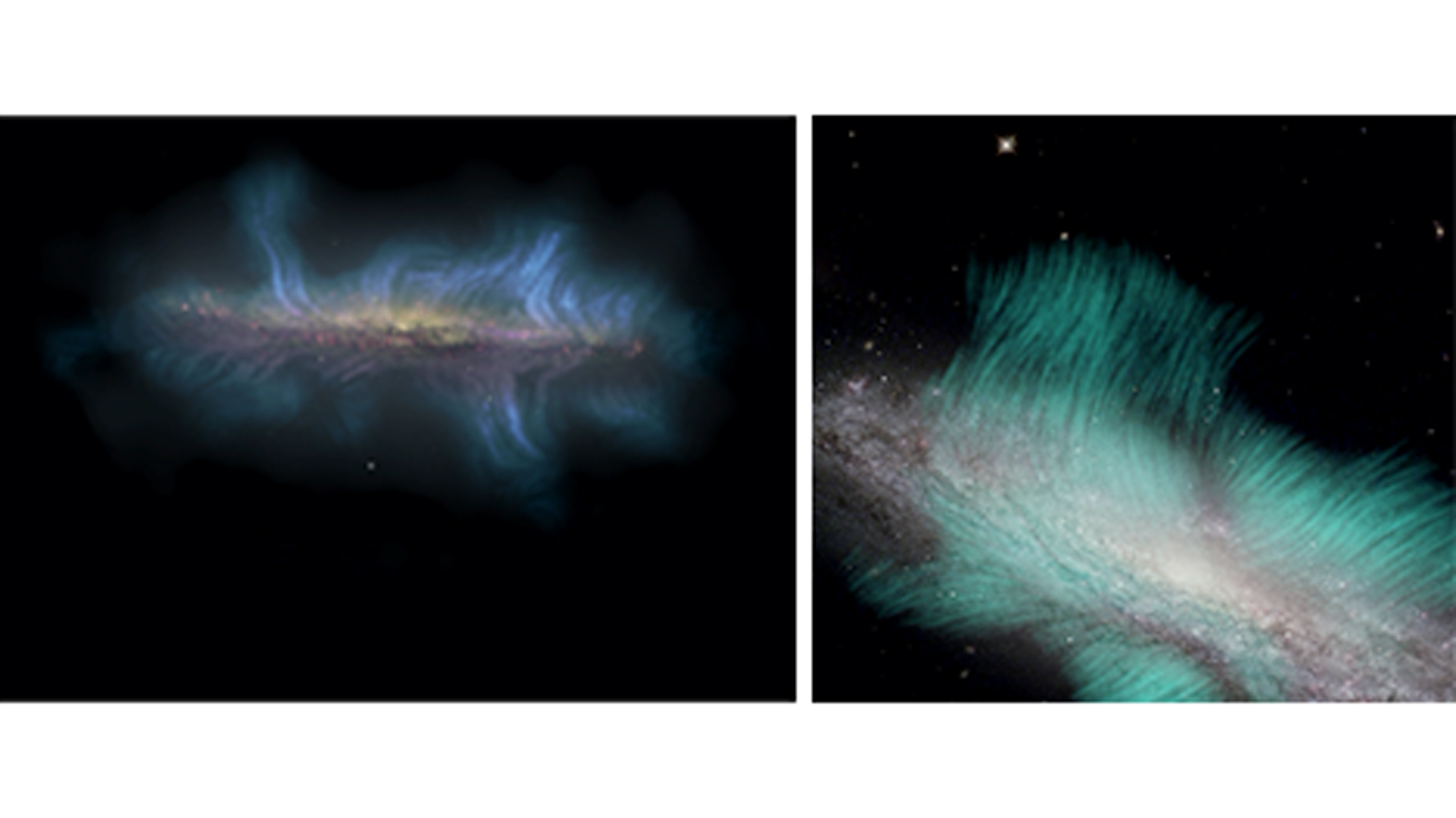

English’s cosmic image, submitted to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory’s image contest, is a composite image constructed with data from the Hubble space telescope and the Very Large Array (VLA), a radio telescope. The image shows the extended magnetic field of the galaxy NGC 5775.

Many people may think cosmic images are simply photographs from space, but these images are actually constructed from data. English said the public has trouble understanding the information scientists collect in its original form, so “space photography” is more accurately a visual representation of that data rather than literal pictures.

Light is understood as an electromagnetic wave. The electric and magnetic fields are perpendicular to each other, and the light waves move perpendicularly to these fields. Sometimes, the waves may become slightly rotated. The radio telescope helps image-makers determine the degree of rotation, which is called the polarization angle.

To construct the images, these polarization angles are drawn as vectors. A random noise field is put down and the vectors are placed on top of that and then joined with a line integral convolution algorithm, which traces the change in orientation of the magnetic field lines on the sky.

“So, it’s not a snapshot of the magnetic field lines,” English explained.

“It’s actually a tracing of the radio astronomy data — polarization angles on the sky.”

Interestingly enough, all the data used is in black and white, and the image-maker is responsible for assigning colours.

English is a member of the CHANG-ES consortium (Continuum Halos in Nearby Galaxies — an EVLA Survey), an international collaboration using the VLA telescope to study the evolution of galaxies.

“Galaxies aren’t static — they change with time, and we want to know the role of magnetic fields in changing galaxies over time,” English said.

“So, we’re measuring, in an image like the one I did, the magnetic fields [and] how they’re moving away from the disc of the galaxy.”

To understand the role of magnetic fields, CHANG-ES studies their structures within galaxies.

“When we know what the structure is, that structure will constrain the origin of the magnetic field,” English said.

“So, we will be able to determine whether magnetic fields are formed in galaxies due to, say, the galaxy rotation, or whether magnetic fields were part of the universe and so galaxies are born with magnetic fields.”

To generate magnetic fields on Earth, she explained, the protons and neutrons in the molten core are charged and separated from each other. This generates an electric current, and the rotation of Earth and other similar bodies generates a magnetic field.

CHANG-ES seeks to discover whether this is also the case with galaxies.

“As long as you have an electric current flow, you are going to generate a magnetic field, and vice versa,” English said.

While the data involved with creating astronomy images is modern, English believes that astronomy has always had an impact on everyday life. To her, experiments over the centuries have been able to cause many societal changes as well as scientific ones.

“Our philosophy [and] our beliefs have become dynamic,” English said.

“And I think that it’s when we look around at the world around us and understand the world around us, and we understand that the world […] [and] the universe around us is dynamic, then it allows our beliefs to be fluid and dynamic as well — they can change with time.”

For those interested in exploring the concepts behind constructing cosmic images like English’s, she teaches a hands-on course called “The Art of Scientific Visualization” in the faculty of science. The course is open to students in their third year and above regardless of faculty as a 4000-level course with no prerequisites, but graduate students can also take it as PHYS 7440.

“It’s how to construct figures and images that use human perception so that it’s supportive of the message you want to get across to your audience, either professional or public,” English said.

“If people want to know how to do this, or are interested in doing for themselves to promote their own research or to communicate more clearly with their colleagues, then anyone from the university is welcome.”