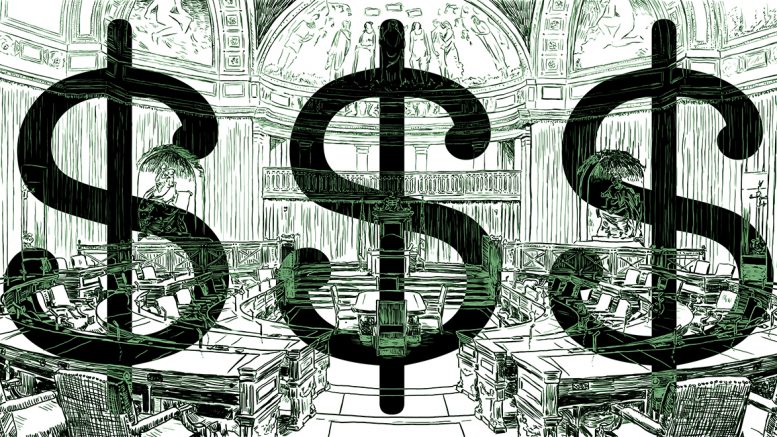

If you envision provincial governments as corporations, then the actions of the Progressive Conservatives make a lot more sense.

Everything comes down to going from the red to the black: cutting social services is just about making your employee’s compensation package a little lighter, and reducing the civil service is really just this year’s round of layoffs in the face of a slumping business cycle. It’s nothing personal, it’s financial.

Except governments are not corporations, and citizens are not its employees. Social services and public programs are not perks governments get to offer as contingent incentives for upstanding citizens: they are necessary goods, period. Nor are the actions of a government simply financial: they are political. And if you are politicking at the governmental level, your actions ultimately have very personal effects on the people who did – and did not – vote you into office.

This is a simple political concept the provincial government has not yet grasped, as shown by its reliance on the advice of private consulting firm KPMG. And this advice has solely to do with the government keeping a lid on the market-value of its spending, as in, only spend if you can earn in turn. And the advice has a market-value of its own: brace yourselves, fiscal conservatives, for public officials paid financiers $ 740,000 to be told to cut down on public spending because it is not turning a profit.

The report describes the way citizens interact with government service a “customer demand,” a callous label premised on a fundamental misrepresentation of the relationship between government and broader society.

Its ranking of so-called “value lenses” delegates quality of service to a humble third priority behind problems of economy and efficiency – the latter two being more concerned with delivering services as fast as possible in order to push costs as low as they can go. Who’s in for a game of moral limbo?

Finally, KPMG has solved one of the storied problems of politics. What kind of balance should be struck between principles and practicalities? Simple: throw principles in the dustbin of history, so long as it saves you a cent or two.

As miserly as they come, lowlights of the KPMG audit included recommended cuts to the Manitoba public housing program, a model deemed “unsustainable” by the consulting firm because it wasn’t unearthing gold coins for state coffers.

The private firm also advised pressuring universities to change their funding models such that programs which directly funnel students into meeting market demands would be rewarded with more funding.

In the same way that social housing is not a housing market, university is not a factory of labour power. While there is a place in higher education for training individuals and developing a specialized, practical skill set, there are virtues in a university education that extend beyond pay grades and professional networking. To suggest otherwise is to allow the abstract engine of a fictional marketplace to churn out our value judgements, and in a world rife with products from the T.V. infomercial-sphere, this is not something we should be wont to do. Students of the arts and sciences have just as much a place on their campuses as do their applied counterparts.

If the government and its crony consultants see their market dystopia to fruition, the university programs that fail to bring top dollars to market in the form of fresh graduates will be gutted for all they’re worth.

Where is the humanity in walking all over the humanities?

One can imagine the provincial government simpering to KPMG when the former first took office, desperate for what Progressive Conservative officials took to be practical know-how on spending and saving, as if the private financial organization was a self-help guru of the likes consulted by Oprah. “Penny for your thoughts?”

Except thoughts come with a cost heftier than mere pennies in the private-sector, and using public funds to loosen private lips so they may whisper in the ear of government – on the best ways to cut social services and public programs, no less – is a perversion citizens should not pay for.

In fact, it’s a perversion that should not exist at all. But when we live by the verdicts of the market, anything goes, so long as you slap a dollar sign on it.