Social media has been a part of campus life at the University of Manitoba for years – but some new apps are exposing the darker side of social media platforms that allow anonymous users to publicly mock and deride their fellow students.

One of those apps is YikYak, a social media platform established in 2013 that allows users to communicate on a discussion thread that is only accessible to those within a 1.5-mile radius.

YikYak has generated considerable controversy in primary and secondary schools in North America, resulting in the app being banned from several schools over so-called cyberbullying concerns.

There was a lockdown at an Ottawa school in January when a gun reference popped up on YikYak, and police in Charlottetown have reported that many students are refusing to go to school because they cannot take being exposed to the comments on the app’s discussion thread.

Last week, the ugly side of the app was exposed at the U of M after students took to YikYak to discuss the candidates running for the executive of the University of Manitoba Students’ Union (UMSU). Comments about the women running for UMSU executive positions ranged from debates on the attractiveness of candidates to assumptions about their intelligence due to their physical appearance as well as explicit sexual comments.

Among those on the receiving end of these remarks was Bénédicte LeMaître, a candidate for vice-president external as part of the Strong UMSU slate. LeMaître, who garnered 1,208 votes, lost the election to Wilfred Sam-King, who received 1,299 votes.

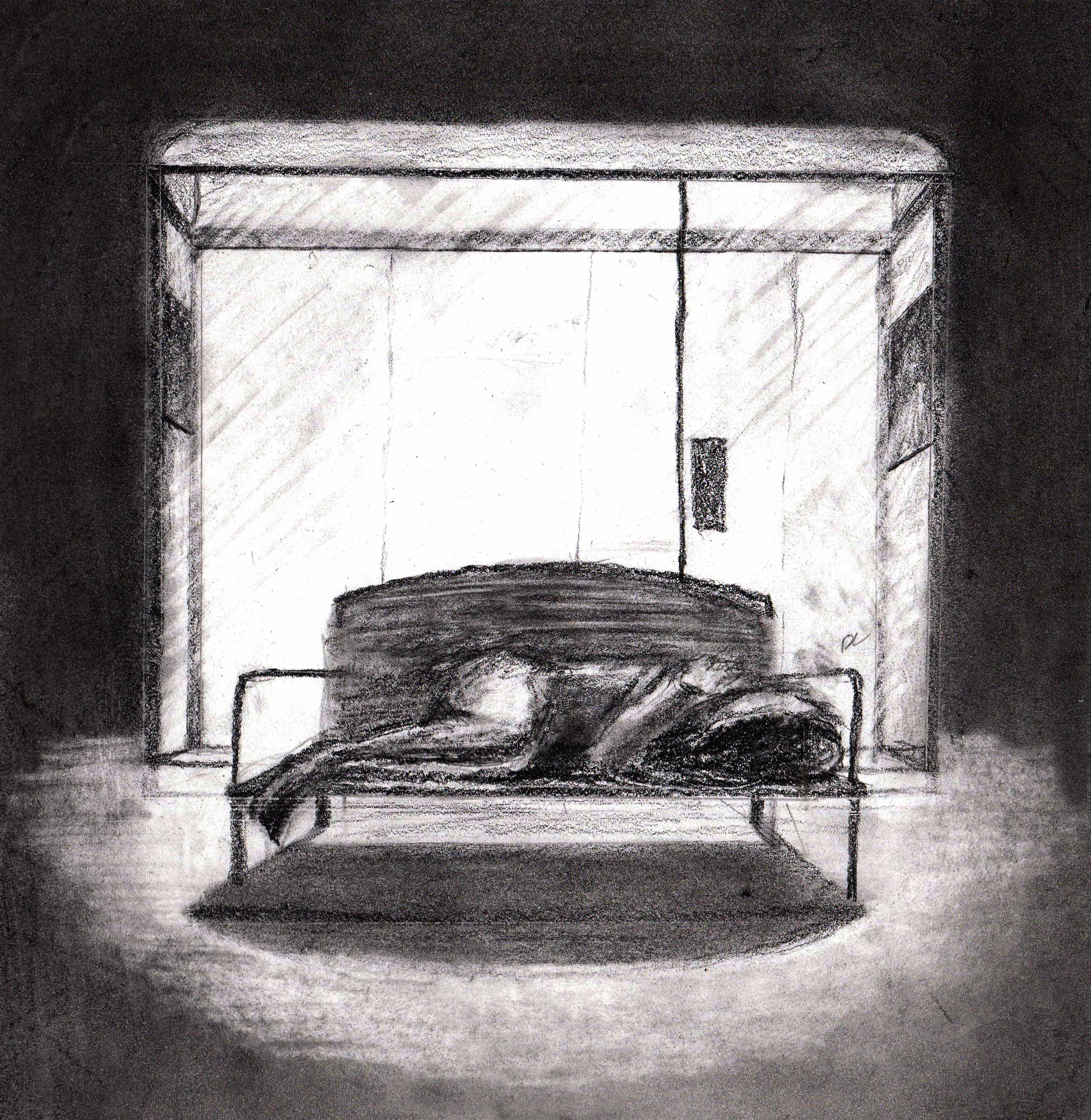

“This affected my campaigning because I constantly felt like I was under scrutiny by students at the university. I would walk around campus and people would look at me and I would wonder if they were the ones writing things about me on YikYak, and I always felt quite uncomfortable,” LeMaître said.

“Anytime I did something, it would either become criticized or sexualized on YikYak.”

From UManitoba Confessions to YikYak

These kinds of posts are not new at the U of M and, as reported by the Manitoban two years ago, they were prevalent on the UManitoba Confessions and UManitoba Confessions 2.0 pages on Facebook.

At the time, the Manitoban spoke to the anonymous administrators of these pages, who publish the submissions they get from students anonymously.

According to the Manitoban’s earlier coverage, sexist and racist confessions get a substantial number likes and shares.

The UManitoba Confessions page has been inactive since May. However, UManitoba Confessions 2.0 is still up and running, though they have been posting less frequently than before, with the most recent post being from a month ago.

YikYak, another place for people to make anonymous posts based on where they go to school, has in many ways replaced it.

Like UManitoba Confessions, YikYak is especially appealing to university students because it’s a place for people to read about issues and comments specific to their campus, promoting a sort of campus culture among the student body, where jokes and stories tend to revolve around life at the U of M.

Just last week alone, posts ranged from complaints about long lines as Starbucks to the weather. However, students also posted explicit attacks on women, international students, indigenous people, and other demographic groups on campus.

Kelsey Hrappstead-Rimke, a U of M student and YikYak user, told the Manitoban that the app is especially popular among students in residence.

“We would all sit around and see what was on there, because oftentimes you can see what’s going on really close to you,” she said.

“Lots of times it was a way to figure out where the parties are before socials and things like that.”

Trevor Toffan, a U of M student and former YikYak user, said that the anonymity of users means that many students feel they can make rude and racist comments that they would not post elsewhere.

“It’s part of the allure for some people because a lot of people are scared to voice their opinions on Twitter, for instance, where it can be traced back to you as a person. I think it gives cowardly people an outlet on the Internet,” Toffan said.

“In general it’s an okay thing as long as people don’t act on what they say. Some people just need to get it out of their system.”

Jennifer Clary-Lemon, associate professor in the department of rhetoric, writing, and communications at the University of Winnipeg and specialist in new media, expressed concern but also cautioned against viewing these apps as inherently nefarious.

“Students have always sought out ways to communicate that are out of reach from parents and teachers – in many ways, YikYak is the modern-day equivalent of passing notes in the classroom,” she told the Manitobanin an email.

“With an anonymous note in class, one is able to narrow the perpetrator down to the 30 or so people in the classroom. On an app like YikYak, that’s nearly impossible.”

When asked how universities can respond to this issue, Clary-Lemon emphasized that these apps need to be put in their context: YikYak is what Myspace was a decade ago. And because university students are adults, universities should treat them as such and not take steps to ban the app or to use other coercive measures.

“One of the best ways to spoil a good back-channel gossip mill for students is to make it a place for everyone – that means that faculty, student services, administrators, university communications, and marketing departments all need to start using the technology,” Clary-Lemon said.

“In using anonymous geolocative virtual spaces for a variety of means to situate university life – rather than only to fuel gossip, hatred, or fear without repercussion by those between the ages of 18-24 – we not only undergird their community-oriented, communicative function, but we also make that anonymous gossip-mongering note a lot less fun to pass around.”

U of M response

Despite the growing popularity of social media, and the controversy surrounding YikYak in particular, the U of M doesn’t have a broad social media policy applicable to the entire campus.

According to Karen Meelker, access and privacy officer at the U of M, while certain faculties may have their own faculty-specific social media policies, there is currently no overarching one for the university.

Meelker also told the Manitoban that even though the university is a public space and students can take photos on campus, photos taken with the intent of publicly shaming someone crosses the line into disrespect, and can therefore be addressed by the U of M’s Respectful Work and Learning Environment (RWLE) policy.

According to Jackie Gruber, human rights and conflict management officer at the U of M, online activity can trigger the policy if a complainant brings it forward through the human rights and conflict management office as a case of discrimination, sexual harassment, or personal harassment.

Students who post sexist, racist, or homophobic content can be investigated and disciplined because the comments made would be considered a form of discrimination, she said.

The RLWE policy is in the consultation stage of its revision as part of the larger behavioural policy review process that the university is undertaking.

According to Gruber, the revised policy will be more specific and clear about its ability to respond to incidents of disrespect that occur on social media to ensure that students are more aware of their responsibilities to each other.

According to Meelker and Gruber, their offices work closely together when incidents occur online that may breach either the privacy policy, RWLE policy, or both. It is largely done on a case-by-case basis.

When asked what can be done when these policies are breached by someone who is anonymous, like on YikYak, both Gruber and Meelker acknowledged the difficulties this posed, and the unique way anonymity can encourage disrespect or prompt generally unacceptable comments from students who feel empowered by the knowledge that the post cannot be traced back to them.

Meelker noted that when there have been extreme cases on other campuses in North America, such as when threats are made, the YikYak company has willingly worked with police and universities to hand over the identities of the individuals making the threats. Therefore, students should not rely on the assumption that their anonymity is protected at all costs when they post socially unacceptable content on YikYak.