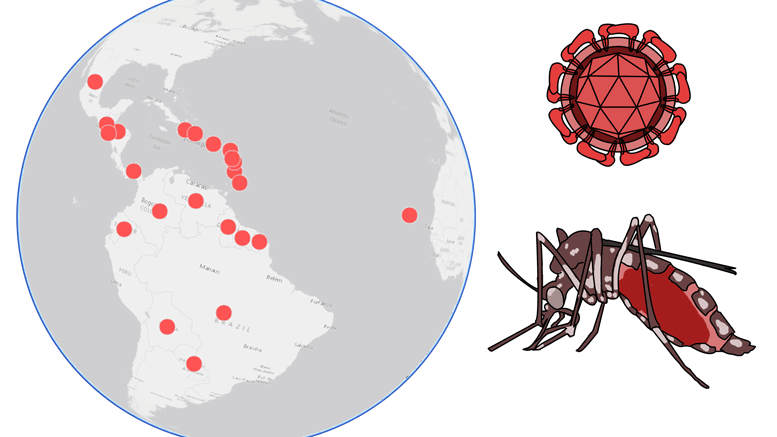

Only two years after the Ebola crisis in West Africa caused thousands of deaths and worldwide fears of its rapid spread, a new epidemic looms threateningly over the world. The Zika virus, which has now been declared a public health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO), has flared up in Latin America. So far the virus has been detected in nearly all countries between Mexico and Paraguay.

Zika virus is an infection that is particularly detrimental to pregnant woman and has severe symptoms including mild fever, conjunctivitis, and headache, according to the WHO. There is no vaccine or treatment available for the virus.

For pregnant women, it is suspected that the virus can cause microcephaly in fetuses, meaning the baby will be born with an unusually small head and underdeveloped brain.

Women who are already pregnant and living in places where the virus is widespread have been advised to go for regular checkups and ultrasounds.

The disease originated in Africa, but spread to Brazil in 2015 and is now rampant in the Caribbean and parts of North and South America.

The governments of Colombia and El Salvador are urging women to delay getting pregnant for two years until the disease can be properly controlled.

Unlike Ebola, Zika virus is not spread through bodily fluids or human carcasses, but through mosquito bites.

Zika is transmitted by mosquitoes of the genus Aedes, which are not native to Canada.

Zika has been around for quite some time, surfacing in the 1940s in Uganda before billowing down below the radar.

Peter Pelka, assistant professor in the University of Manitoba’s department of microbiology, spoke to the Manitoban about the virus.

“Zika virus is indeed a micro borne disease but seems to be stationed within tropical locations at the moment,” Pelka said.

“The problem arises if someone travels to Brazil, gets bitten and infected, then comes back to Canada and [the virus] survives in a different mosquito.”

Another question to ponder is whether the disease is present in other mosquitoes besides Aedes, Pelka said.

Pelka believes that governments asking women to avoid getting pregnant is a short-term strategy until a more sustainable solution can be developed.

“The reason for that approach is to prevent children born with birth defects, particularly microcephaly. This is partially due to the effects of the virus, which affects neurons and essentially the developing brain of the child,” he said.

“I think the approach to preventing pregnancy altogether is a temporary approach at the moment. Long term, you simply cannot stop people from getting pregnant.”

Pelka said that preventing the spread of the Zika virus is difficult because it’s hard to stop mosquitoes from biting.

“The problem with mosquitoes is that they bite all the time so we’d have to wear protection all the time. Furthermore, fogging and pesticides are not a solution. Thus it’s really difficult to eradicate an issue like this,” he said.

“You cannot eliminate it obviously, but it depends on the virus as there may be ways of treating the viral infection. But generally viruses are notoriously difficult. However, I think if you stop people from getting pregnant for a couple years, you can certainly reduce the number of birth defects that way, and in that time develop a vaccine.”

As to why the Zika virus has re-emerged after decades of stagnation, Pelka said there are several possibilities.

The most obvious one was that the virus had mutated since the 1940s, causing a new and much more aggressive strain than before. He hypothesized that the mutation may have allowed the virus to spread more rapidly.

Another theory Pelka believes may explain this re-emergence is encroachment into new territory. The fast pace of Brazil’s expansion is causing people to venture into new areas. Pelka said these people may be at risk since they do not have immunity to pathogens they have never encountered before.

Pelka said that this was the case with the Ebola crisis last year.

However, Pelka said that the Zika virus “does not kill the host, but instead wants to coexist with the host and survive.”

However, while the host may survive with the virus, it has detrimental impacts on unborn children, as has been seen with the increase in microcephaly.

Pelka said that Zika virus is a part of the genus Flavivirus, which includes West Nile and Dengue. The virus consists of “single-stranded RNA genomes which means these viruses are often more prone to mutations and alteration of genomes.”

“Vaccinations may be more difficult to find as a result and would have to be updated periodically,” he said.

The WHO has scheduled an emergency committee meeting for Feb. 1 to determine how the organization will respond to the Zika virus outbreak.