In Canada, given our seemingly welcoming and generous culture, we are often quick to condemn highly popularized police brutalities and debates over immigration policies in the United States. We do not always, however, lend the same attention to our own history of racism.

In her controversial new film Ninth Floor – which was screened at Winnipeg’s Cinematheque on Jan. 30 as part of Canada’s Top Ten Film Festival – Chinese-Canadian director Mina Shum (Double Happiness and Long Life, Happiness & Prosperity) reminds Canadians of their own history with civil rights by detailing the events of the mostly forgotten (and still unresolved) 1969 Sir George Williams Riot that took place at Montreal’s now-defunct Sir George Williams University.

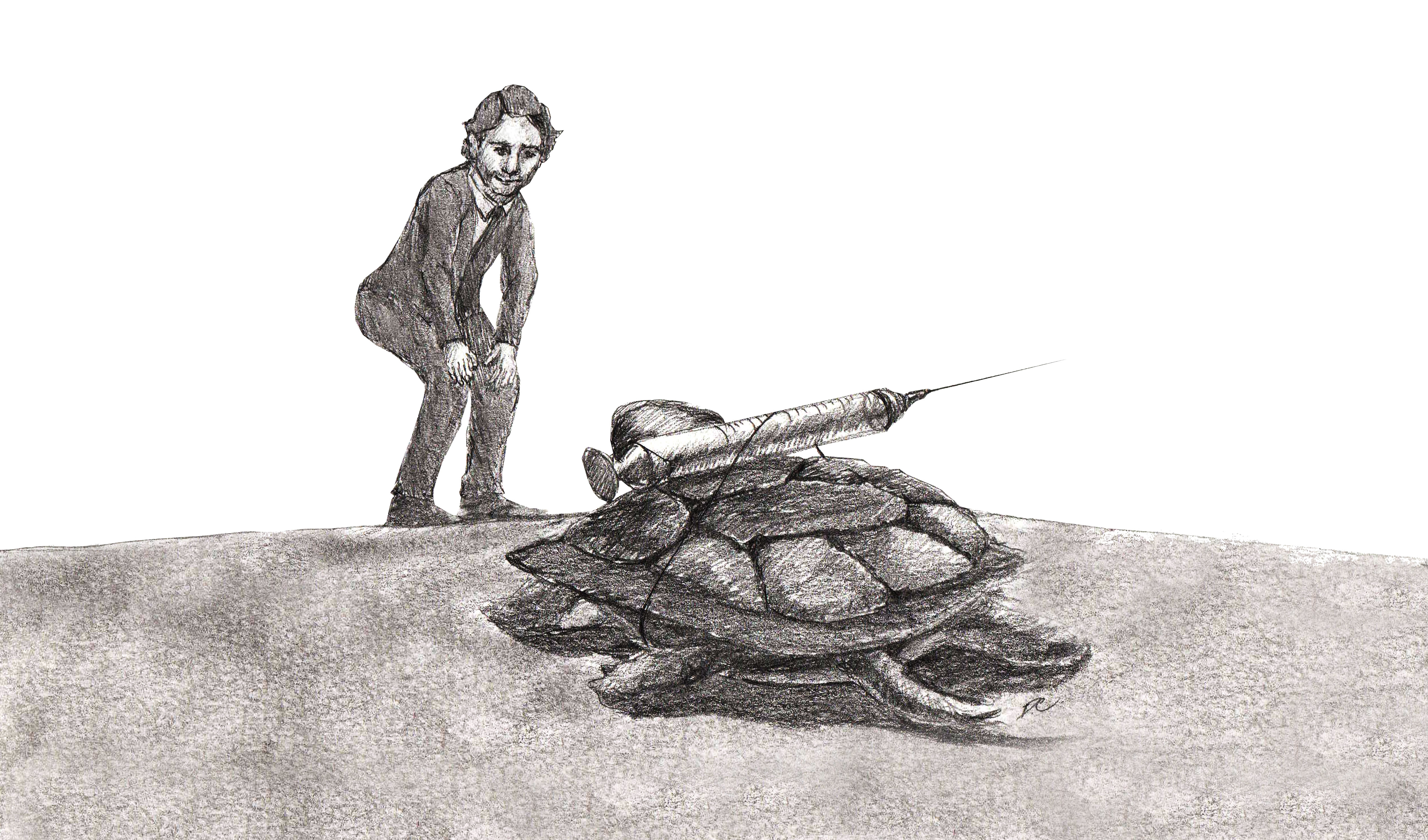

What began as allegations of racism against assistant biology professor Perry Anderson from six black students turned into the student occupation of a computer room on the ninth floor of the university’s Henry F. Hall Building within a year.

The university administration’s perceived intransigence in handling the allegations ten months later led to over 400 students storming out of a meeting with the university board to stage a 14-day peaceful occupation.

In the movie, scenes of peaceful student protesters trapped by a fire assumed to have been set by the police – as the crowd outside the building chant racial slurs and threaten violence – top off the display of vitriol from both university and police officials. It’s reminiscent of the riots and social justice movements of Ferguson, Mo. and Baltimore, Md.

The university’s actions gave the impression that they had no responsibility to students of colour and how they were treated. In other words, this educational institution refused to provide appropriate service to a group of people because of their colour – this is, by definition, institutional racism.

“Somewhere along the line, the implicit assumptions of slavery had become institutionalized,” Rodney John, one of the six biology students who started it all, says in the film.

Today, many of the Sir George Williams student protesters and their families are being haunted by the stigma they had faced from the press at the time.

Kennedy Franklin, one of the leaders of the protest, returned to his home in Trinidad after the incident and is said to have struggled with mental illnesses.

“The very nature of the [newspaper] headlines created such a stigma for everybody who was involved in this incident that everybody buried it,” said Selwyn Jacob, the film’s producer, via Skype at the Winnipeg screening.

“These people have carried this shame and stigma for the last four decades. The message is that [people should] view this film as a cautionary tale.”

Via surveillance tapes and interviews with some of the original complainants and other related parties, Shum’s narrative presentation of the controversial case gives the audience a first-hand, subjective view of how the affair unfolded.

However, some of the interviews and topics were not as forthright or as representative as they perhaps should have been. For example, Perry Anderson’s son and Kennedy Franklin’s daughter represented their parents in the film, but this only affords the viewer a second-hand experience.

The events that happened on that ninth floor in 1969 aren’t common knowledge among Canadians. With her film, Shum gives us an opportunity to both remember the students’ plight and be more socially aware.

Ninth Floor was released in 2015 and produced by the National Film Board of Canada. Learn more about the movie at www.nfb.ca/film/ninth_floor