Since the beginning of this school year, students at the University of Manitoba have been bombarded by a rising number of messages promoting consensual sexual relations and critiquing rape culture.

With controversies surrounding orientation week celebrations on campuses over the past few years, universities across Canada have intensified their fight against sexual assault from a framework that they claim bolsters mutual consent and empowers both partners in sexual encounters.

Rebecca Kunzman, vice-president advocacy at the University of Manitoba Students’ Union (UMSU), said that her student organization has teamed up with students, faculty, and administration to raise awareness about the issue on the U of M campus.

“We know that most sexual assaults that occur on campus occur in the first six weeks of class,” said Kunzman.

Given the number of social events integral to orientation celebrations, such as student-run socials and informal parties where alcohol and other intoxicating substances may be consumed, Kunzman said that these events are the driving factor behind sexual assault statistics on campuses.

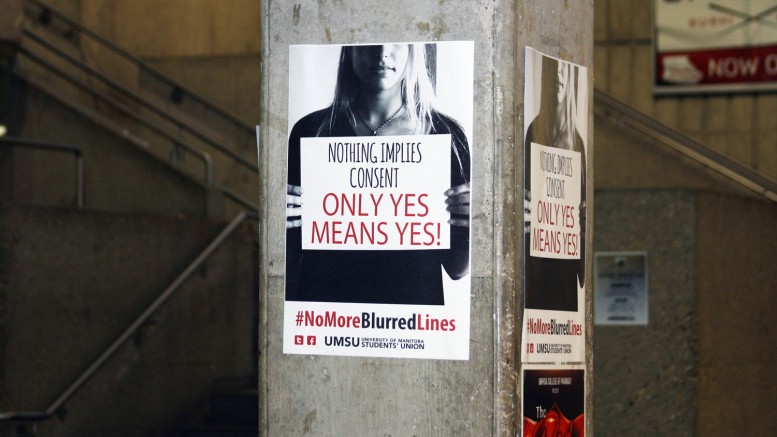

Last fall, U of M student Wanda Hounslow, in conjunction with sociology instructor Mary-Anne Kandrack – both members of the U of M Sexual Assault Working Group – spearheaded the #NoMoreBlurredLines campaign to promote consent culture and target the issue of sexual assault at the University of Manitoba.

Hounslow said that the #NoMoreBlurredLines concept originated from the controversial 2013 song released by Robin Thicke, “Blurred Lines.” Critics of the song argued that the lyrics promote victim-blaming messages and implied that consent can be ambiguous.

Recently, Hounslow partnered with UMSU to promote consent culture at their Frosh Music Festival as part of the “Nothing implies consent. Only yes means yes!” initiative.

In contrast to the popularly coined “No Means No” campaign advocated by the Canadian Federation of Students and picked up by various nation-wide student organizations to combat rape culture, many universities have been shifting toward more sex-positive messages implied by “Yes Means Yes” initiatives to drive what they call a culture of consent.

“Unless you hear a yes, nothing else is consensual when it comes to consent. We are trying to end the blurred lines about consent and sexual activity,” Kunzman said.

The university has been devising its own resources, workshops, and other initiatives about consent culture, driven by a small group on campus. Frosh Festival “codes of conduct” have been plastered across campus to draw widespread attention to the problem.

Citing the Winnipeg-based Klinic Community Health Centre, the U of M has defined sexual assault as any of the following acts – whether verbal, emotional, or physical – without consent: sexual contact, violent or aggressive sexual attacks, unsolicited sexual comments, harassment or threats that make one feel uncomfortable, violated, or under attack, touching without permission, forced kissing or fondling, and oral, anal, or vaginal penetration (rape).

Klinic describes consent as an ongoing, voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activities.

From January through the end of August there were three reports of sexual assault under investigation at the university, according to information from the U of M security services provided by John Danakas, executive director of public affairs at the U of M.

Katie Kutryk, health and wellness educator at the U of M, said in an email that most incidences cast under the university’s broad definition of sexual assault are unreported.

“Keep in mind that ‘reported numbers’ of sexual assaults are highly unrepresentative of what actually goes on,” she said.

The legal definition outlined in the Canadian Criminal Code states that a person may be convicted of assault, including sexual assault, for intentionally applying force against another without consent.

Consent is not obtained where the complainant submits or does not resist by reason of the actual application of force, threats or fear of the application of force, fraud, or the exercise of authority.

If the accused alleges that they believe that the sexual act was consensual, then sufficient evidence must be provided and reviewed in court to consider the presence or absence of reasonable grounds for that belief.

University of Manitoba law professor Karen Busby said consent should be “continuous and contemporaneous.”

“Most of the time you don’t actually get the spoken word ‘yes,’ but if there are indications of no and less-than-enthusiastic, or any kind of hint that there isn’t a yes, then that means there’s a no,” Busby said.

“If there is ambiguity about whether or not there was a yes, there isn’t a yes.”

Busby admitted that allegations of sexual assault can be difficult to convict, as typically there are only two witnesses: the complainant and the defendant.

In court, cases must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, which, Busby said, is usually in favour of defendants.

“In cases of incapacity or inability to consent, then we cannot assume consent. In some situations, consent is not possible,” Busby told the Manitoban.

“Criminal charges are one thing, but what you want is for people to be in healthy balanced relationships. In the past, and sometimes today, some men perceived that once they are aroused, they have the right to release, and we need to challenge that.”

Some laws surrounding consent have evolved, although advocates argue that attitudes toward consent have not.

“There have been a lot of interesting cases in the news in recent years where lawyers or judges will give these horrible messages that aren’t in line with consent culture, in speaking about the victims’ clothing or how they were carrying themselves […] So we do see the need for these kinds of campaigns,” said Alana Robert, UMSU women’s representative, who also founded the Justice for Women Student Group at the U of M.

“It’s an issue on our campus, whether systems or witnesses are reporting it, as a lot of the time sexual assault goes underreported, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.”

This story has been updated from its original print version to include new information on U of M sexual assault statistics.