The Sept. 5 issue of the Globe and Mail had no less than 22 articles directly or indirectly dealing with just one picture: that of the body of a three-year-old Kurdish boy, Alan Kurdi, lying face down in the sand. He drowned, along with his mother and brother, while they were trying to reach the Greek island of Kos, and thus the European Union.

There is nothing new about refugees drowning in the Mediterranean Sea as they try to reach Europe. More notable than what is captured by the photograph is the response that has come of it.

That response has been, to put it mildly, sickening. From both governments and individuals, the knee-jerk proclamations of horror and sudden offers of help don’t stem from compassion. They stem from guilt and a desire to distance ourselves from that guilt, lest as individuals and institutions we be forced to confront our own part in the tragedy. We hope that if we proclaim horror now, no one will remember that a few days ago we had not even compassion.

The Syrian civil war has been raging for four years. Hundreds of thousands of people have died, surely including many toddlers. Certainly no shortage of refugees meeting tragic ends. But we weren’t confronted with the image of their lifeless bodies; the thought of these innocent deaths was not in our collective mind.

It’s not just the Syrian civil war. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the ruin of Libya, the slow suffocating death of the Palestinians: there’s no shortage of horrors for people to flee from. But unless there’s a particularly tragic photo, it’s business as usual in Canada.

Maybe an offhand reference here or there – “isn’t it a shame” from individuals, “Canada is doing its part” from the government. But certainly not party leaders tripping over themselves to lay blame, nor 22 articles in one day on the human toll of the “refugee crisis.”

In our rush to proclaim our goodness of heart, our hate of evil, that’s how we have to frame it: a crisis. Not the perfectly logical result of decades of Western imperialism that have turned the cradle of civilization into a hell on earth. Not the predictable result of our unbalanced relationship with the rest of the world.

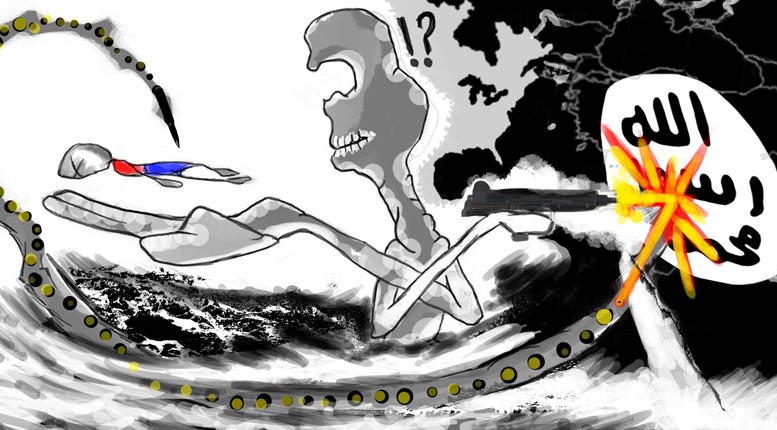

And so our sick, twisted solutions: take in more refugees! Send more humanitarian aid! No mention of halting our imperialism, though. We’ll take in the huddled masses when our conscience leaves us no choice, but forget about ending the bombings and invasions, the culture of waste and continuing Western colonialism, that made them to huddle in the first place.

Stephen Harper, for once, speaks for the majority of Canadians. Of the image of Alan’s lifeless body, he declares: “the first thing that crossed [my] mind was remembering [my] own son Ben at that age,” before launching into a justification of bombing ISIS targets in the boy’s home country.

Tragedy, it seems, is only digestible if we imagine it happening to us. We offer different solutions to the problems of others than we would accept for ourselves. In intellect or in soul, there is a void in the people that think the solution to refugees fleeing the Middle East is more bombings in the Middle East.

But this void is not restricted to our leaders. It exists in all of us. “Bomb the terrorists,” we say, pretending that we believe that drone strikes kill only terrorists, and never three-year-olds. War is only ever waged by the West upon the evil ones of the Earth.

When instability results, when once prosperous and stable nations are reduced to roving bands of fundamentalist militants armed by weapons we sell them, their hospitals and universities and culture rubble, we just ignore it. The reporting stops, we move on to our next target. Even if our goal is ending lawlessness, as with the mission to destroy ISIS, the only solution we seem to be able to conceive of is more bombing.

All is good when you live in the West – until an over-crowded sweatshop where our cheap gadgets were produced collapses. Until our wars of aggression spawn terrorists and refugees. Until we’re forced by an all-too-rare public uproar to confront the costs of our actions. And then umbrage, bubbling over into outrage! “Half-barbarians driven by greed, they must have been, who allowed this to happen,” we say – of people in other countries.

It is easy to judge the varied European responses to the first ripples of the rising human tide of our times: it seems callous and indifferent. But there is nothing here in Canada to suggest that our response would be any different. Certainly, if it was, it would be no thanks to a government which seems more eager to spin numbers on everything from greenhouse gas emission to the number of refugees accepted, than commit to actual change.

Our comfort, peace, prosperity, and happiness are worth nothing if they are built on the backs of others. Our compassion is worth nothing if it is extended to people who are victims of our own callousness. Every day the innocent are dying. And more and more are going to die: as the climate worsens, there will be more refugees. As more and more nations are “sent back to the stone age,” there will be more and more militants to flee from.

The media did an uncommon thing when it showed us the body of that little boy. It forced us for a moment to confront the evil and injustice that exists in the world, the dark shadow to the light of the West. We should fix that image in our minds, and with it there examine all our actions and opinions, asking ourselves what part they (and we) played in that tragedy – and what part of ourselves we are willing to change, to build a future where it does not happen again.