The recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa has placed pressure on pharmaceutical labs worldwide to develop a treatment for those infected and to prevent the spread of the virus.

On July 31, a highly experimental drug in its earliest stages of development was administered to two American patients, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.

The two recipients of the unapproved drug, ZMapp, were Christian aid workers who had been providing medical assistance in West Africa. They contracted the virus through contact with the bodily fluids of patients under their care.

How the virus works

Ebola enters the body through mucous membranes or breaks in the skin. Unlike humans, whose genetic information is stored in their DNA, Ebola’s is stored in the RNA of the virus and instructs it to replicate in invaded cells.

Ebola is an enveloped virus, which means it carries a specific protein that allows for the virus to easily move in and out of cells.

Once inside the cell, the virus injects its RNA, which takes over regular cellular function – ultimately transforming it into an Ebola virus factory. The virions are secreted from the cell and join the attack on the immune system.

As the virus gains an upper hand over the immune system, the virus turns its assault on connective tissues, epithelial cells, neurological cells and the interior cells of blood vessels resulting in internal bleeding, tissue damage, and organ failure.

Immune system function and treatment therapy

The experimental drug ZMapp, manufactured by Mapp Biopharmaceutical Inc. based in San Diego, is a serum comprised of three laboratory-made antibodies – two of which were developed at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg.

The Winnipeg team was led by Gary Kobinger, head of special pathogens at the laboratory and adjunct professor in the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba.

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins produced by the immune system in response to germs or viruses. These foreign invaders are also known as antigens. The antibodies produced have binding sites that latch on to the attacking antigen.

So how does this work specific to Ebola? How does ZMapp step in for a compromised immune system?

The group of antibodies utilized in ZMapp are known as monoclonal. This means that they are specifically designed to target only one antigen – in this case, the Ebola virus.

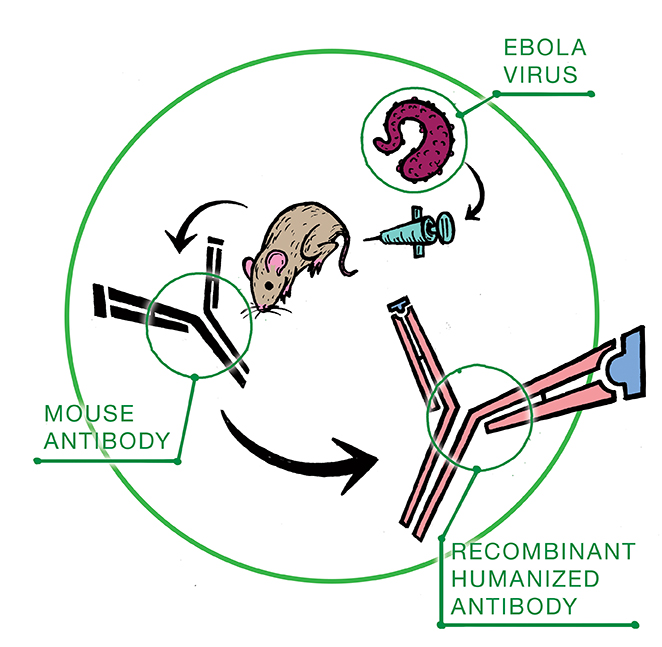

The monoclonal antibodies are first developed in mice injected with Ebola. The antibody-producing cells are fused together with cancer cells to produce a cell that continues to divide, making only one type of antibody: clones.

Three antibodies harvested after this process were identified to have binding sites that bound to Ebola.

Mass-producing clones

Before these antibodies can be administered to humans they must first undergo a process known as humanization in order to make them compatible with our immune system.

“The antibodies are humanized using molecular engineering techniques,” explained Sam Kung, associate professor in the department of immunology at the U of M.

Simply put, this process entails replacing some of the mouse antibody protein components with human proteins.

The next step is mass production. This is where “Big Tobacco” does something laudable.

Kentucky BioProcessing, a subsidiary of Reynolds American (the second-largest tobacco company in the United States), applied their position as a worldwide leader in plant protein expression, extraction, and purification to amplify the production of ZMapp.

The tobacco plants used are a relative of the kind used in cigarettes. They are selected for biotech applications because their biology is well-known, they are low maintenance, and they grow rapidly.

A piece of DNA from the monoclonal antibodies is taken and inserted into the tobacco plants. These plants produce the mouse/human anti-Ebola antibodies just like they would make any other protein.

The resulting treatment was tested through the laboratory animal hierarchy, from mice to primates, before it was administered to Brantly and Writebol.

1,500+ and counting

As of Aug. 26, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that the death toll from the Ebola outbreak has reached 1,552, while 3,062 have succumbed to infection. The World Health Organization warns that cases of the Ebola virus could exceed 20,000 as the disease spreads across West Africa.

The effectiveness of ZMapp is still uncertain. The race to develop a vaccine to prevent the spread is still underway, and will be the next breakthrough in the control of Ebola outbreak.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stresses that, “the most effective way to stop the current Ebola outbreak in West Africa is meticulous work in finding Ebola cases, isolating and caring for those patients, and tracing contacts to stop the chains of transmission [ . . . ] and having health-care workers strictly follow infection control in hospitals.”