Last Wednesday the University of Manitoba unveiled a new indigenous graphic novel collection, which is to be permanently housed at the Elizabeth Dafoe Library.

The extensive collection contains some 200 pieces from both native and non-native authors, but all the titles have indigenous peoples as their subject matter. Camille Callison, the indigenous services librarian at the U of M, compiled the collection.

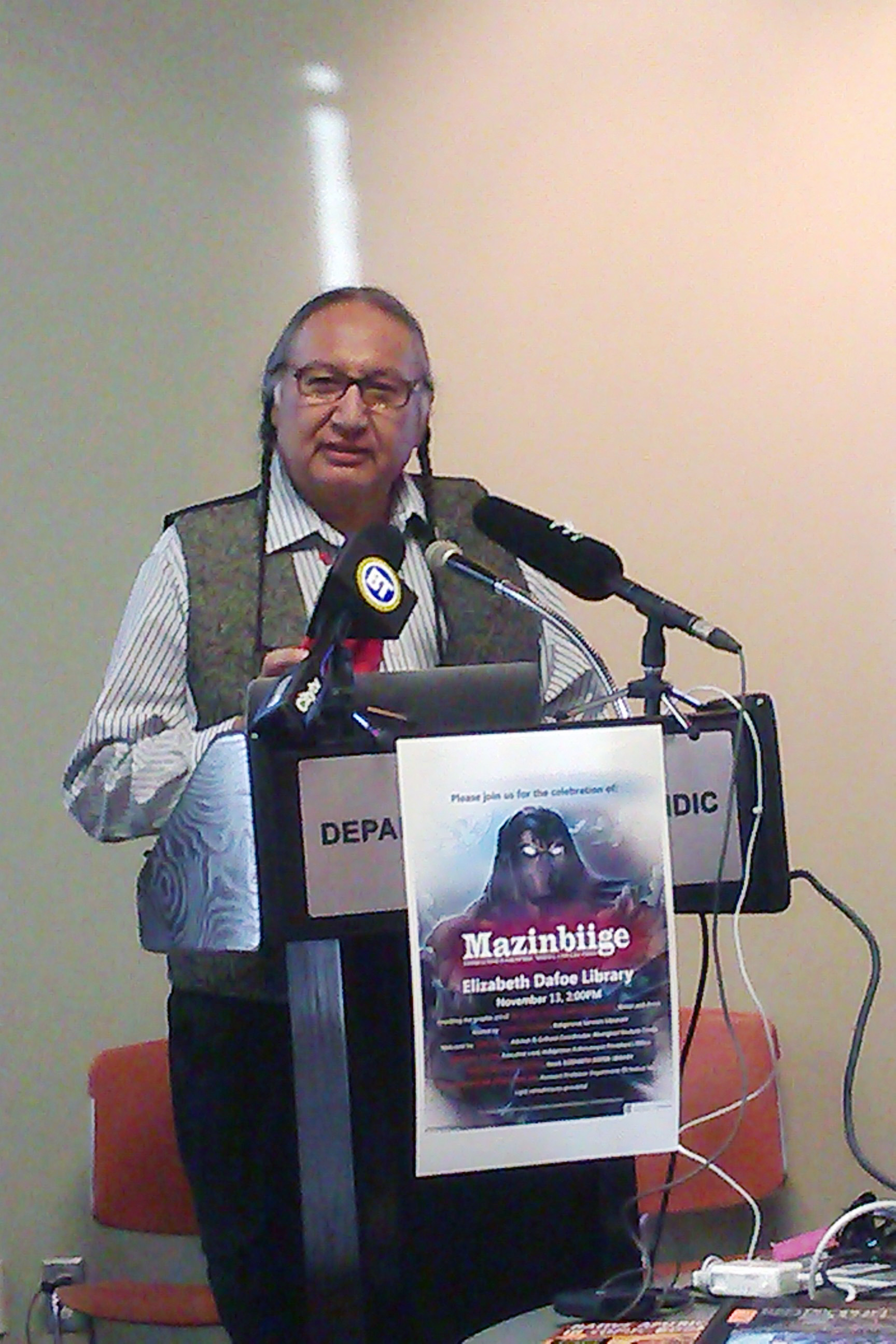

The event was well-attended and included an opening prayer from Carl Stone—who is a student advisor and instructor for the Aboriginal Student Centre at the U of M—the artwork of First Nations artist Jay Odjick—whose work appears in some of the titles—and a lecture from Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, assistant professor of native studies, about graphic novels and comic books as a literary genre.

Sinclair teaches a course at the university on indigenous graphic novels entitled “Super Savages and Aboriginal Images in Graphic Novels.”

“Graphic novels are the collaboration of words and images to tell stories and histories. They bring together imagery and words in a very powerful way,” Sinclair told the audience in his opening remarks.

He introduced some concepts useful to analyzing graphic novels, and later spoke to the Manitoban about the emerging importance of graphic novels as a literary genre.

“Comic books have traditionally not been very friendly to indigenous people, portraying them as stereotypes, and in rather inhuman ways. But this genre has been something that indigenous people have really adapted as their own, and made really meaningful,” said Sinclair. “It’s amazing how many indigenous artists and writers are now in the graphic novel or comic book genre.”

Callison worked closely with Sinclair to put together the collection, in part to support the course Sinclair is now teaching.

“I first got the idea for this from trying to indigenize the collection of our libraries and indigenize the space [ . . . ] and because there was a course being taught at the academic level, I was able to build this collection. Without that course I wouldn’t have been able to gather and collect all of this material,” said Callison.

Callison emphasized the ethnographic importance of comics and graphic novels in reflecting the attitudes of the larger society, and how that role has changed over time.

“[W]e wanted to show how the portrayal of First Nations people has changed and how graphic novels and comics have either supported or detracted from indigenous people and their struggle for self-determination and decolonization,” said Callison.

Three students from Sinclair’s class will be publishing their own graphic novels.

“Some students from the class read a native story by Warren Cariou, [an associate] professor here at the U of M, and adapted it into a graphic novel and are having it published. I think it’s awesome,” said Sinclair.

Callison highlighted the importance of graphic novels and comics in reaching new audiences, especially young people.

“People who wouldn’t have picked up a book and read about some of these issues will pick up a comic book or graphic novel and can learn about native histories and cultures. For young First Nations, this is really becoming a powerful tool to reconnect them to their culture.”

The collection will be available on reserve for students and staff.