Most of you were probably taught that “extinction is forever.” Heck, you may have even bought a T-shirt with that logo on it, hoping that your fashion sense or financial support might stem the tide of some cataclysmic species disappearance (of which you have the general sense is due to happen next week sometime). In truth, extinction is most often a gradual process that requires clever planning and a good deal of political will to reverse.

The animals that most likely come to mind when the topic of extinction is raised are the cute and “fubsy” mammals, like the Giant Pandas who seem to get all the sympathetic press. Suffice it to say one does not often think of insects in the context of extinction. Indeed, given their staggering abundance, most Manitobans might say we could use a little more extinction in that area, especially in the blood-sucker department. Yet believe it or not insects are just as vulnerable to the ill effects of human endeavours as other animals. One particular example of this is the bumblebee.

According to the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (yes, the British have one of these) the UK once had 27 species of bumblebee, more than 10 per cent of which are now nationally extinct. Why does this matter? Well, besides providing an ideal name for kid’s soccer teams, the primary role of bumblebees is as a pollinator, or fertilizer of flowers. To fertilize an ovule inside a flower and subsequently make seeds, the pistil of a flower must receive pollen (plant sperm) from another flower. The transfer of this pollen between flowers can be achieved with wind or direct contact, however bees also play a very important match-making role.

In fertilization, the unsuspecting bee is attracted to the flower by its nectar. While collecting nectar some of the flower’s pollen dust gets stuck on the bee’s hairs. The bee then leaves to find another flower taking the pollen with it. When it collects from another flower some of the previous flower’s pollen is brushed off onto the new one’s “ovary,” allowing cross-pollination, or fertilization to occur. Bumblebees — which are hairier than honey bees — are better at transporting the tiny pollen grains on their hairs from one flower to the next.

Besides pollinating wildflowers, in nature bumblebees are also pollinators of such commercially important plants as alfalfa, field beans and rapeseed. In fact, alfalfa cannot be pollinated by honey bees; it must be done by bumblebees.

Unfortunately these ecologically and commercially important insects are threatened by the loss of wildflower areas — from which the bees gather nectar — to intense farming. In addition, the British extinctions have been encouraged by the loss of hedgerows in which the bumblebees would often build their nests.

Despite this gloomy news there is hope for at least one species of bee, which was recently declared extinct in Britain in 2000. The shorthaired bumblebee is scheduled for reintroduction into Britain from New Zealand where the species still exists.

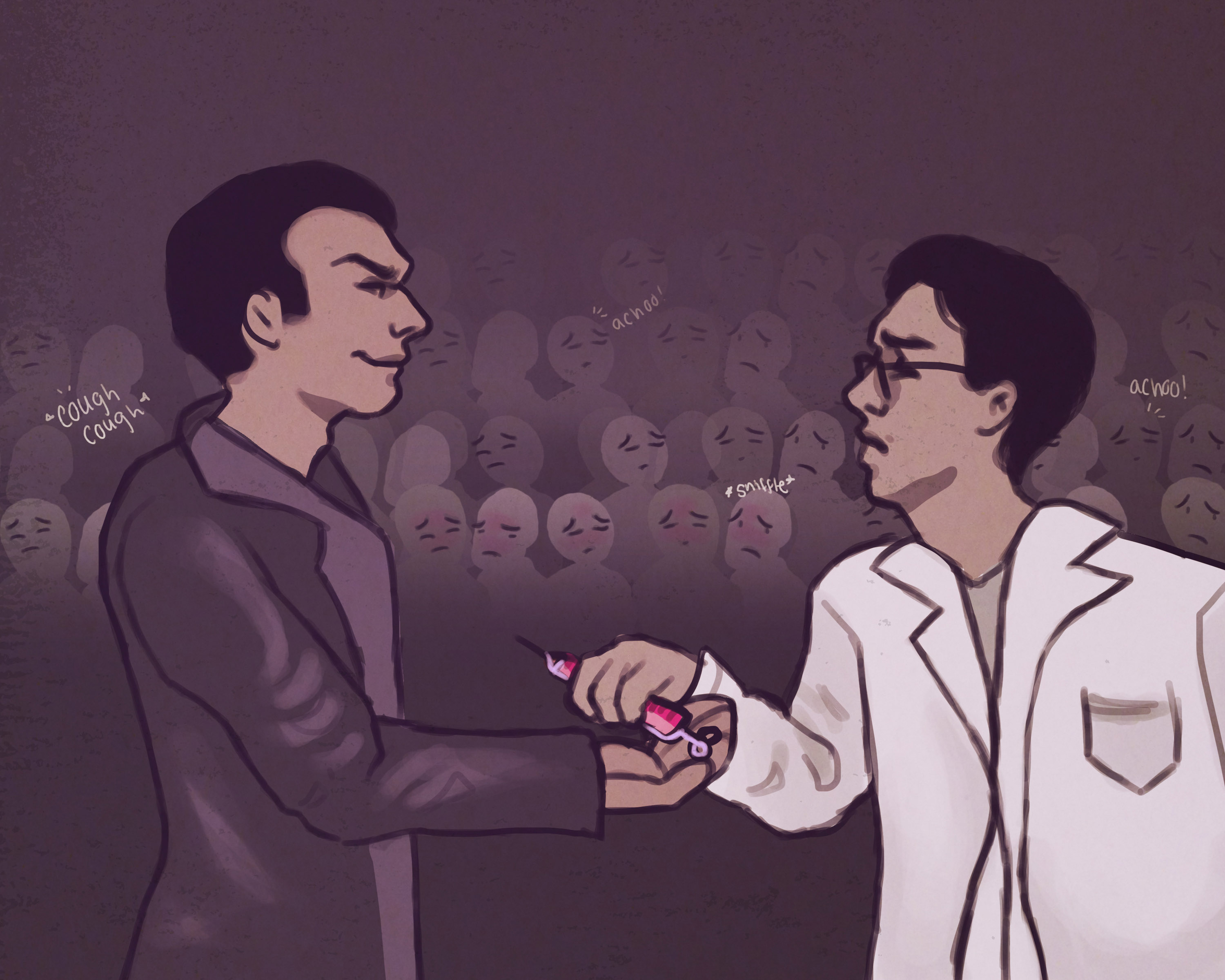

The process of reintroducing the bees has finally had its last major hurdle solved. Firstly, a team in New Zealand will capture as many shorthaired bumblebee queens as possible as they are emerging from hibernation. Next, in order to prevent the spread of bee diseases back to Britain, a generation of the bees will be bred in captivity. Since this species of bee is very difficult to breed in captivity this presented a large problem for the team. Fortunately, a Czech bumblebee enthusiast named Jaromir Čížek discovered that if the queens were fed fresh pollen — which is full of protein — collected by other bumblebees everyday, they could be made to breed well enough in captivity to accomplish this goal.

Once the next generation is produced, they will be kept in hibernation and flown to Britain where they will be released into the wild. It is hoped that this release will take place in spring of 2010.

Farmers and landowners in the area where the last of these bees were spotted before extinction have been cooperating for several years with the project team to ensure that land is dedicated to growing the right sorts of flowers for the bees. With this concerted effort the shorthaired bee will hopefully flourish once more.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this story is that the bees, which the team will be capturing from New Zealand, were originally brought from Britain. In one of the more successful stories of species introduction, the shorthaired bee, along with three other species of bumblebee, were brought to New Zealand in 1885. The purpose of their introduction was to pollinate red clover, which the shepherds of New Zealand wanted for their pastures; the long tongue of these species of bee, as Charles Darwin had noted, made them well-suited to do just that. The species took to the south island successfully and are now abundant. Now these colonial descendants will be making a trip back to the land of their origin. It appears that — ironically, considering the amount of damage it has caused worldwide — species introduction, in this case, served to fend off the greater evil of extinction.

Unfortunately for our bees, North America does not seem to monitor its bee populations as closely as does Europe. A survey of eastern North America conducted from 2005-07 revealed that three bumblebee species (Bombus affinis, B. pensylvanicus, and B. ashtoni) have all but disappeared from areas where they were found as recently as 1970, when a survey of the region had identified 14 different bumblebee species. We in North America would be wise to learn from our British cousins the value of such natural pollinators and adopt supportive gardening practices to aid in their survival. It is fortunate that the shorthaired bumblebee will likely survive, but we cannot count on an extraordinary story like this one to save all these species. So, while it seems that in the case of the shorthaired bumblebee extinction was only temporary, this is undoubtedly the exception to the adage that extinction is forever..